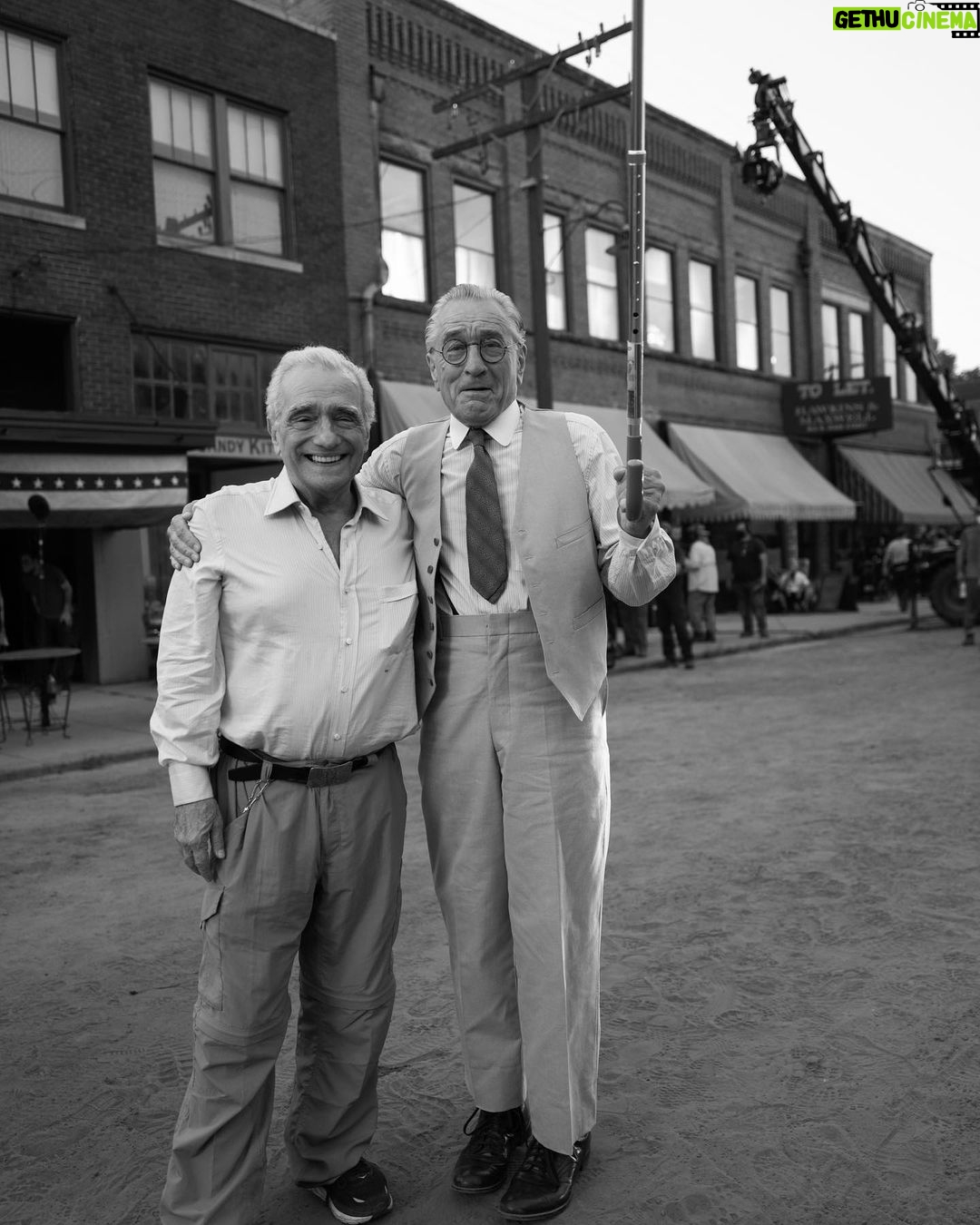

Martin Scorsese Instagram – Repost from @thefilmfoundation_official

•

To read Kent Jones’ post this week about CRISIS (1963, d. Robert Drew) click the link in The Film Foundation’s bio.

@ethandre

#filmrestoration #cinema #film #movie | Posted on 04/Jun/2020 21:44:37

Home Actor Martin Scorsese HD Photos and Wallpapers June 2020 Martin Scorsese Instagram - Repost from @thefilmfoundation_official

•

To read Kent Jones’ post this week about CRISIS (1963, d. Robert Drew) click the link in The Film Foundation’s bio.

@ethandre

#filmrestoration #cinema #film #movie

Check out the latest gallery of Martin Scorsese