Lisa Ray Instagram – Posted @withregram • @janicepariat Perhaps because this year we’ve spoken so much about illness, and because I’ve been unwell lately (terrible cold but nothing worse, thankfully)—I’ve been thinking about the act of recovery. It sounds old fashioned: convalescence. A word that comes to us from the mid-17th-century, from the Latin “convalescere”, meaning “to grow fully strong”.

In these times of quick-fix medication, we aren’t used to long illnesses (which is no bad thing) but we aren’t accustomed to slow recuperation either. Unlike the historical practice of viewing convalescence as a distinctly separate and important stage of illness recovery, today’s convalescents are expected to dive straight back into normal life. To be strong, and able almost immediately. But what must we do with the “after-life” of illness?

This, I realise, is when we require most compassion. Writer Alain de Botton says “People can accept you sick or well. What’s lacking is patience for the convalescent.” It’s true—perhaps to convalesce is to grow stronger because it forces you to be patient—with others, with yourself.

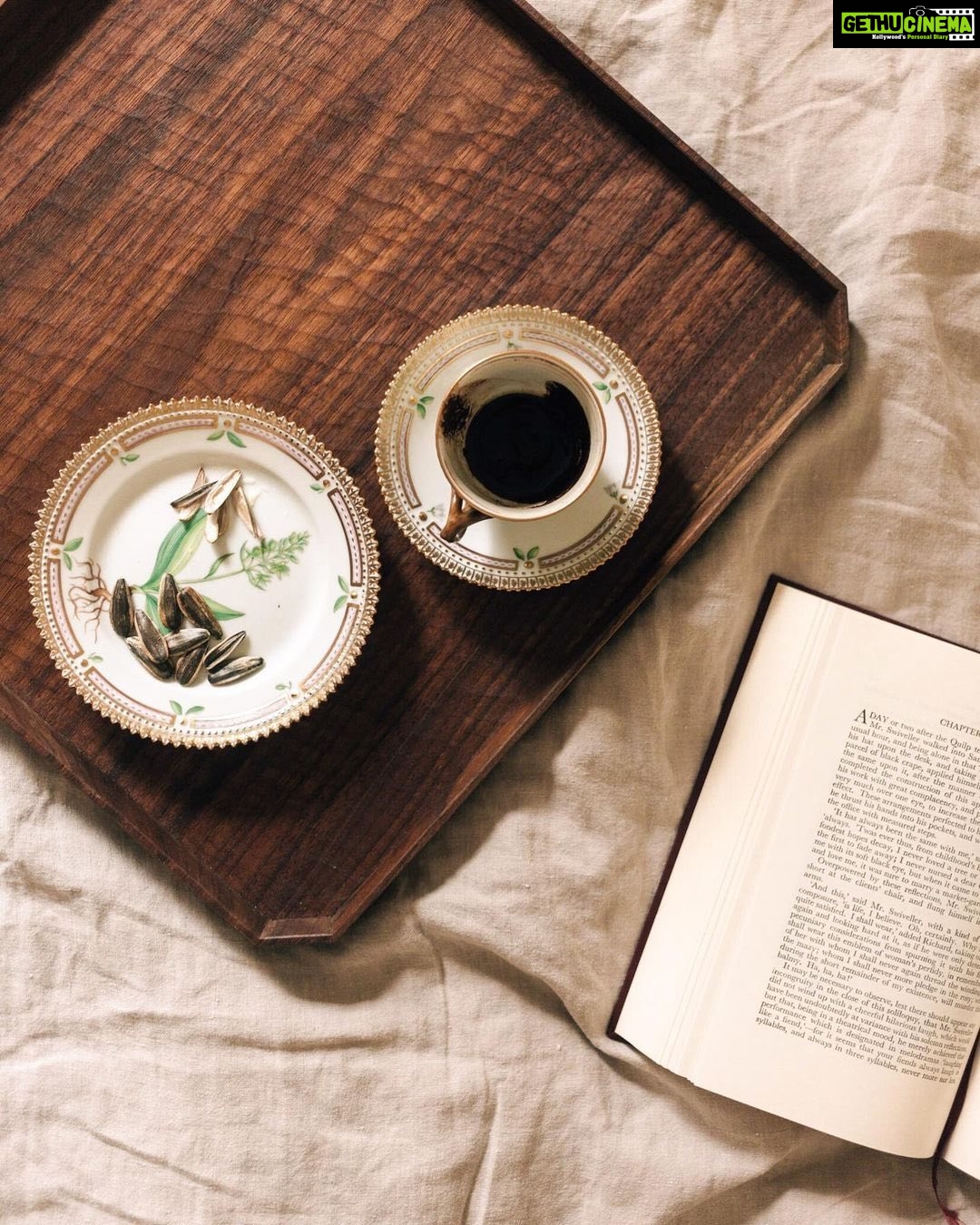

These days, I’m learning to lie here, shifted during the day, like a theatre prop, from the bedroom to the living room from where I can look out into our little garden. I cannot stare at a screen, so I read, listen to music. At times, I’m impatient, dismayed. I realise I need to learn to do nothing. It’s hardest of all—and easier perhaps when I was younger.

In a description from a book about recovery—historical, personal, political—Bernard Schlink’s “The Reader”, the young protagonist has suffered a bout of Hepatitis: “These are hours without sleep,” he says, “which is not to say they’re sleepless, because on the contrary, they’re not about lack of anything, they’re rich and full. Desires, memories, fears, passions form labyrinths in which we lose and find and then lose ourselves again.”

My days convalescing begin to take this turn into a dreamy, out-of-time state. To recover, I learn, is to recuperare, to “get again”, and so we must give away these hours, this time, in order to get ourselves back again, changed, more resilient, stronger.

.

.

.

.

📷 @erol | Posted on 15/Oct/2020 11:42:00